Understanding the molecular basis of SCA6

Understanding the molecular basis of SCA6 suggests a therapeutic strategy.

In summary:

- 1. The CACNA1A gene encodes two proteins, called α1A and α1ACT. A mutated form of α1ACT causes the neurological symptoms associated with SCA6 to develop during adulthood.

- 2. Synthesis of α1ACT relies on an element called IRES. In a mouse model of SCA6, blocking IRES activity – thereby blocking α1ACT synthesis – alleviates neurological symptoms.

- 3. α1ACT plays a very important role during early life in the mouse, while the cerebellum is still developing. However, blocking α1ACT synthesis in adulthood does not cause adverse effects.

- 4. It is therefore hoped that it will be possible to develop a drug that can be safely administered to adult humans to selectively block α1ACT synthesis. The best type of drug to achieve this may be a designed antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), which could be used as a therapy for all SCA6 patients.

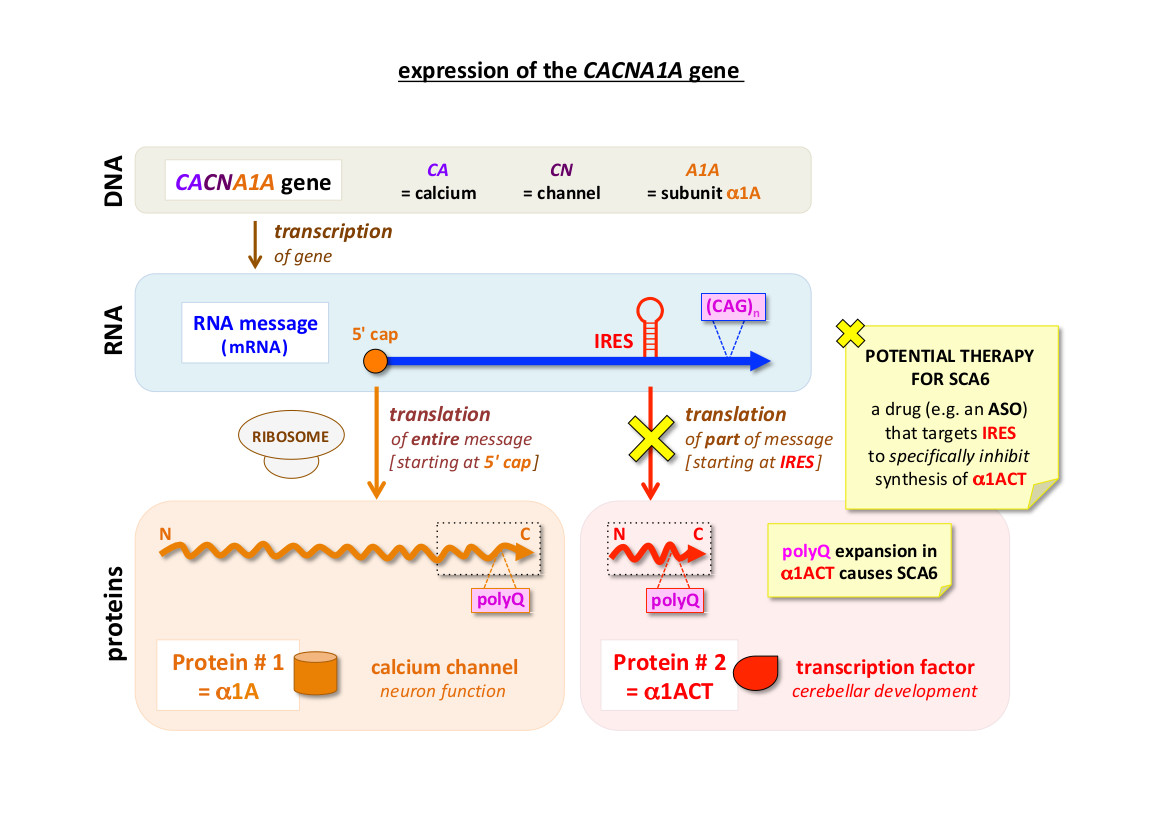

The causative agent of SCA6, and how it is made

To express the information encoded by a gene (e.g. CACNA1A), it must first be transcribed into an intermediate RNA message (mRNA).

This can then be read by ‘molecular machines’ called ribosomes, which translate it into protein.

A protein is synthesised as a chain of amino acids, starting at its N-terminus (N) and finishing at its C-terminus (C).

Signals within the CACNA1A mRNA show ribosomes where to start translation.

When ribosomes bind to the 5' cap, they read the whole of the message and the protein product (α1A; over 2500 amino acids) is the

main pore-forming subunit of a membrane-spanning voltage-gated calcium channel – this allows the passage of calcium ions and is important

for neuron function. However, when ribosomes bind to the IRES (Internal Ribosome Entry Site), they only read the last part of the message

and the product is a smaller protein corresponding to the C-terminal part (approx. 550 amino acids) of α1A – hence the name, α1ACT.

The Gomez lab discovered the IRES mechanism for α1ACT synthesis, and showed that α1ACT functions as a transcription factor,

entering the nucleus and controlling the expression of an array of genes important for cerebellar development.

SCA6 is described as a polyglutamine (polyQ) expansion disease – because it is caused by an increase in the length of a tract of glutamine amino

acid residues encoded by consecutive CAG codons near the end of the CACNA1A gene [(CAG)n]. The genetic test for SCA6 counts the number of CAG

codons (ie. the number of glutamine residues); for example, n = 22 is a common pathogenic length. The polyQ tract is located within both α1A and α1ACT.

Expansion of the polyQ tract in α1A does not appear to interfere with channel function. The Gomez lab showed, using a mouse model of SCA6, that expression

of α1ACT containing an expanded polyQ tract (n = 33) within cerebellar Purkinje cells is sufficient to cause symptoms of ataxia.

In humans, n = 33 is the largest pathogenic expansion found so far. Note: because the mouse gene does not encode a polyQ tract, all

mouse models have a ‘humanized’ gene – ie. part of the mouse Cacna1a gene has been deliberately replaced by the equivalent part of the human CACNA1A gene.

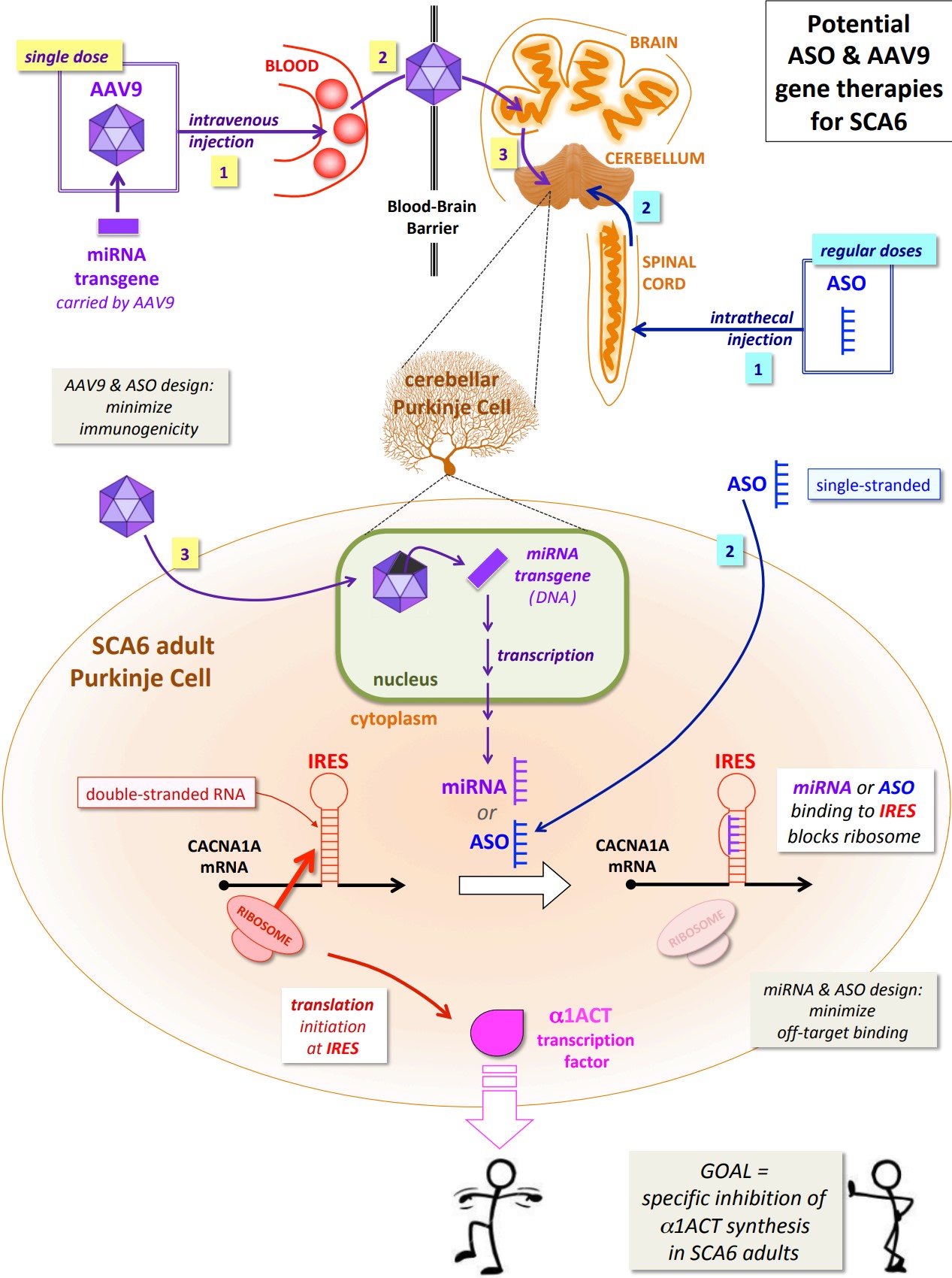

α1ACT synthesis can be blocked by targeting IRES

The Gomez lab then developed a new mouse model in which α1ACT expression is driven by the CACNA1A IRES, as well as being specific to Purkinje cells.

As before, expressing expanded α1ACT (n = 33) in adult mice caused ataxic symptoms. Excitingly, these symptoms could be alleviated by co-expressing (ie. at

the same time as α1ACT), a naturally occurring human micro RNA (miRNA) that inhibited synthesis of α1ACT by binding to the IRES and interfering with the

initiation of translation by ribosomes. Importantly, since silencing α1A expression would be lethal, this particular miRNA (‘miR-3191-5p’) specifically

inhibited α1ACT expression, without interfering with α1A expression. (Note: miRNAs are very short pieces of RNA, originated by transcription and used by

the cell to help control gene expression.) Existing FDA-approved drugs were also screened for an ability to selectively inhibit α1ACT expression in cultured

cells – four candidates were identified, and are being further investigated. (‘Small molecule inhibitors’ related to these may have therapeutic value in the future.)

These studies show that it is possible to selectively block α1ACT expression.

α1ACT is essential in early life, but is dispensible in adulthood

Using yet another mouse model, in which the expression of α1ACT in Purkinje cells can be switched off when desired by feeding a drug called doxycycline, the

Gomez lab has analysed the role of normal α1ACT (ie. with a non-expanded polyQ) during development. In mammals, the cerebellum is not yet fully developed at

birth. It turns out that α1ACT plays a crucial role in cerebellar development during a short neonatal time window, and that switching off its expression in

adult mice has little effect on the cerebellum. Therefore, it may be possible to safely treat SCA6 in adult humans by administering a drug that selectively

blocks expression of α1ACT, preventing the development of symptoms. An ASO drug targeting the CACNA1A IRES would aim to reproduce, and improve on, the therapeutic

action of the miRNA described above. (Note: a miRNA is an unmodified nucleic acid that can be readily degraded. An ASO is a nucleic acid with various chemical

modifications designed to enhance stability, uptake into cells and target binding, and to minimize toxicity.)

If α1ACT is important in early life, why are people who have inherited SCA6 not affected in childhood, only developing symptoms in adulthood? Evidence indicates

that the polyQ expansion in α1ACT is a ‘gain-of-function’ (rather than ‘loss-of-function’) mutation. Toxic mutant α1ACT protein would cause damage to the

cerebellum – and hence ataxia – in the context of a ‘later life’ pattern of gene expression. In early life, it would still be able to perform its essential functions;

and of course most SCA6 patients express some normal α1ACT anyway, from the normal gene inherited from the unaffected parent.

KEY RESEARCH PAPERS

In 1997, a paper in the journal ‘Nature Genetics’ reported that SCA6 is caused by a mutation in the CACNA1A gene, located on chromosome 19.

A 2013 paper from the Gomez lab (published in ‘Cell’) revealed that CACNA1A actually encodes two separate proteins – it is therefore described as ‘bicistronic’.

Key results from the 2013 paper, and from subsequent papers published in 2016 (‘Science Translational Medicine’) and 2019 (‘Neuron’) – both also from the Gomez lab –

are described here.

GLOSSARY

follow this link for a technical Glossary